A farsighted Pirandello

In recent months I have tried to carry out some research and investigations on the technology in relation to the effects it can induce on human behavior and the possible reduction of creativity and imagination that it could causes (see previous articles in this blog and the seminar “Tecnoscience and Science of Man”).

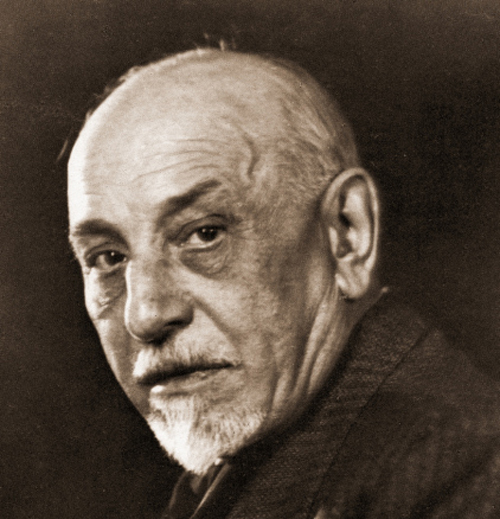

As I continued to reflect on this issue, in a relaxing time I came across – quite by chance – with a page of the novel “Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio operator” of Luigi Pirandello (Italian dramatist, novelist and poet, Nobel Prize for Literature in 1934), which I reproduce below.

As I continued to reflect on this issue, in a relaxing time I came across – quite by chance – with a page of the novel “Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio operator” of Luigi Pirandello (Italian dramatist, novelist and poet, Nobel Prize for Literature in 1934), which I reproduce below.

I have found that Pirandello, about 90 years ago, had already said so simply yet so incisively everything that I was laboriously trying to clarify to myself, to my listeners and my potential readers in recent months.

The novel was written by the great Italian artist in 1925, just when the Futurist movement (and a consistent train of positivism of the nineteenth century) praised the machines and technology as fundamental elements of human development. From here, Pirandello’s persuaded controversy against this idea, well outlined in this and the following pages of the novel.

I satisfy, by writing, a need to let off steam which is overpowering. I get rid of my professional impassivity, and avenge myself as well; and with myself avenge ever so many others, condemned like myself to be nothing more than a hand that turns a handle.

This was bound to happen, and it has happened at last!

Man who first of all, as a poet, deified his own feelings and worshipped them, now having flung aside every feeling, as an encumbrance not only useless but positively harmful, and having become clever and industrious, has set to work to fashion out of iron and steel his new deities, and has become a servant and a slave to them.

Long live the Machine that mechanizes life!

Do you still retain, gentlemen, a little soul, a little heart and a little mind? Give them, give them over to the greedy machines, which are waiting for them! You shall see and hear the sort of product, the exquisite stupidities they will manage to extract from them.

To pacify their hunger, in the urgent haste to satiate them, what food can you extract from yourselves every day, every hour, every minute?

It is, perforce, the triumph of stupidity, after all the ingenuity and research that have been expended on the creation of these monsters, which ought to have remained instruments, and have instead become, perforce, our masters.

The machine is made to act, to move, it requires to swallow up our soul, to devour our life. And how do you expect them to be given back to us, our life and soul, in a centuplicated and continuous output, by the machines? Let me tell you: in bits and morsels, all of one pattern, stupid and precise, which would make, if placed one on top of another, a pyramid that might reach to the stars. Stars, gentlemen, no! Don’t you believe it. Not even to the height of a telegraph pole. A breath stirs it and down it tumbles, and leaves such a litter, only not inside this time but outside us, that–Lord, look at all the boxes, big, little, round, square–we no longer know where to set our feet, how to move a step. These are the products of our soul, the pasteboard boxes of our life.

What is to be done? I am here. I serve my machine, in so far as I turn the handle so that it may eat. But my soul does not serve me. My hand serves me, that is to say serves the machine. The human soul for food, life for food, you must supply, gentlemen, to the machine whose handle I turn. I shall be amused to see, with your permission, the product that will come out at the other end. A fine product and a rare entertainment, I can promise you.

Already my eyes and my ears too, from force of habit, are beginning to see and hear everything in the guise of this rapid, quivering, ticking mechanical reproduction.

I don’t deny it; the outward appearance is light and vivid. We move, we fly. And the breeze stirred by our flight produces an alert, joyous, keen agitation, and sweeps away every thought. On! On, that we may not have time nor power to heed the burden of sorrow, the degradation of shame which remain within us, in our hearts. Outside, there is a continuous glare, an incessant giddiness: everything flickers and disappears.

“What was that?” Nothing, it has passed! Perhaps it was something sad; but no matter, it has passed now.

There is one nuisance, however, that does not pass away. Do you hear it? A hornet that is always buzzing, forbidding, grim, surly, diffused, and never stops. What is it? The hum of the telegraph poles? The endless scream of the trolley along the overhead wire of the electric trams? The urgent throb of all those countless machines, near and far? That of the engine of the motor-car? Of the cinematograph?

The beating of the heart is not felt, nor do we feel the pulsing of our arteries. The worse for us if we did! But this buzzing, this perpetual ticking we do notice, and I say that all this furious haste is not natural, all this flickering and vanishing of images; but that there lies beneath it a machine which seems to pursue it, frantically screaming.

Will it break down?

Ah, we must not fix our attention upon it too closely. That would arouse in us an ever-increasing fury, an exasperation which finally we could endure no longer; would drive us mad.

On nothing, on nothing at all now, in this dizzy bustle which sweeps down upon us and overwhelms us, ought we to fix our attention. Take in, rather, moment by moment, this rapid passage of aspects and events, and so on, until we reach the point when for each of us the buzz shall cease.

Luigi Pirandello

The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio operator

1925 – Book I Chapter II